For many, asking for help can be a difficult task. Studies have shown that individuals underestimate the likelihood that someone will help them by as much as 50%, meaning that people are far more willing to help than we may assume. To receive help, however, we have to ask. CivicScience polled over 2,000 U.S. adults on their comfort with asking for help in a variety of different situations. From a high-level perspective, the outlook is positive.

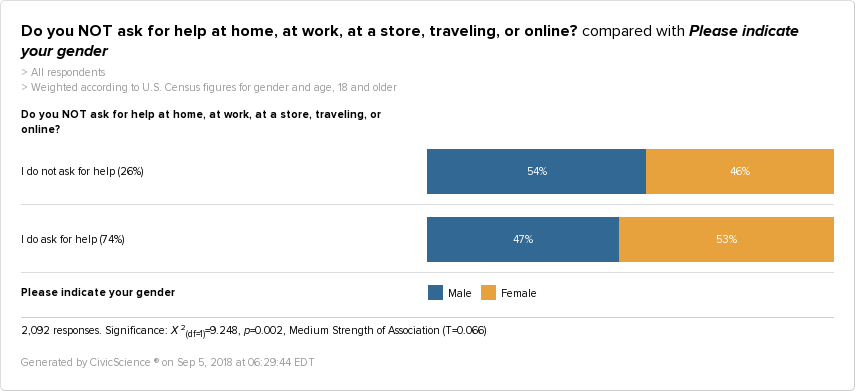

As it turns out, 74% of US adults do ask for help. That’s an overwhelming majority, and a great sign, especially in an age and a society that prioritizes self-reliance.

Help on the Road

Of those who do ask for help, women have a slight lead, making up 53% of U.S. adults who are not afraid to reach out and seek another’s assistance when in need. This may not be surprising, especially to those who have ever grown frustrated with a male spouse, parent or friend, who refuses to ask for help with directions.

However, the data quickly debunks the directions stereotype. Although the gender gap between those who do not ask for help while traveling is quite small, women make up 51% of those who do not ask for directions in this category–something to think about next time you set out on a road trip.

Help in Different Life Stages

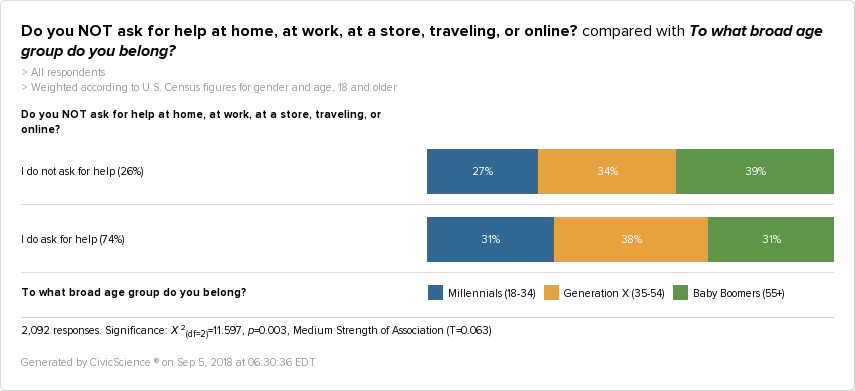

In general, it seems, asking for help may correlate to life stage, but perhaps not in a linear fashion.

39% of those who do not ask for help are Baby Boomers. But, that does not mean that Millennials are the most inclined to reach out when in need. Gen X-ers are the largest group of U.S. adults who feel comfortable asking for assistance, making up 38%.

There are countless reasons why this may be the case, not the least of which is that those in Generation X may be in a place in their life where there is a lot to manage. Gen X-ers are more likely to be married, have a home, be raising kids, all while also holding down a demanding job. The combination of these responsibilities may simply require more help, and, it seems, this is something they are not afraid to ask for.

Help in the Office

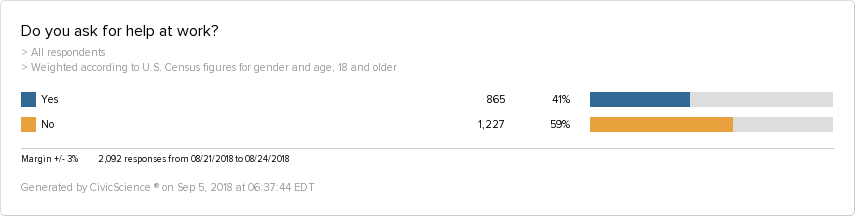

One setting in which questions may arise more naturally is at work. 41% do ask for help in the workplace. That leaves 59% who do not.

The percentage of people not asking for help at work is relatively high, illuminating a potentially concerning situation. Are jobs simply so straightforward that questions are unnecessary? Or, is the environment one in which employees do not feel comfortable reaching out when they need more clarity?

Based on average stress levels, it seems that those who do ask for help at work are far more likely to be stressed out on a daily basis than those who do not. Although this may seem counterintuitive, this suggests that employees who are seeking assistance really may have more responsibilities than they can handle on their own. As a result, asking for help could be more of a necessity than a choice, in order to keep work projects moving forward.

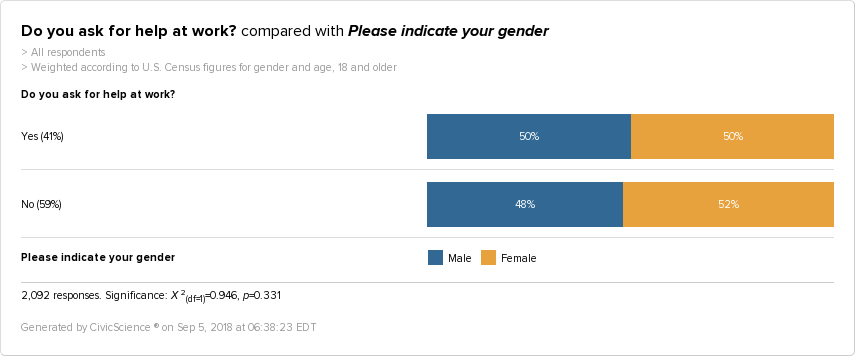

From the perspective of gender, those who do ask for help are split 50/50. However, those who do not ask for help are slightly more likely to be women.

These statistics echo earlier findings around vacation days, where the data revealed that men are more likely to use all of their vacation days than women. With this information in mind, it seems ever more apparent that women may feel they walk a more precarious line in the workplace than their male colleagues. Over time, this unspoken notion of inequality at work could lead to larger consequences, if not directly addressed.

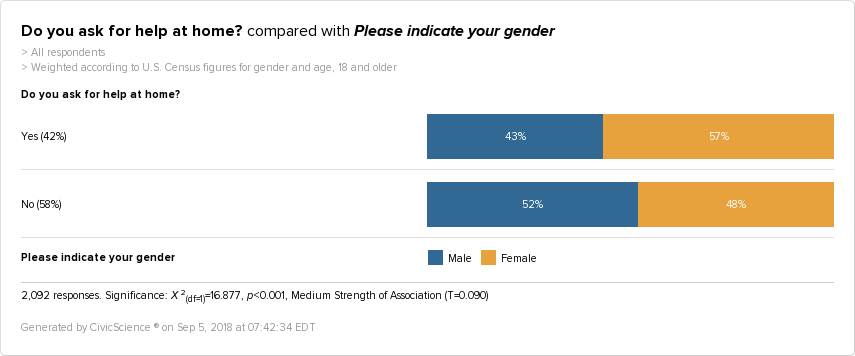

Help at Home

In comparison, women make up 57% of those who ask for help at home.

This sharp contrast from the workplace statistics above suggests that gender continues to play a major role in how individuals behave in public and private spheres, and further, where people feel most supported in speaking up.

If women are more likely than men to ask for help around the house, what does this say about the current culture? And what gender roles do we continue to perpetuate, consciously or subconsciously, in our work and home lives?

If adults do underestimate the likelihood that others will be willing to help, does the rate of asking also correspond to the assumed likelihood of receiving the requested help? It does not seem like too far of a stretch.

Of course, gender is not the only factor in determining who asks for help. Income also likely plays a role.

Those who make less than $50k a year are least likely to ask for help. However, the highest income earners are not the most likely to ask for help. It is, in fact, middle-income earners who are the most likely to reach out when they need assistance.

There are many reasons why this could be the case. It is possible that middle-income earners have more job responsibility, and therefore more potential questions than lower income earners, while also having someone above them to whom they can turn with questions. High-income earners may already be at the top of the workplace hierarchy, and therefore left with fewer options when it comes to seeking advice.

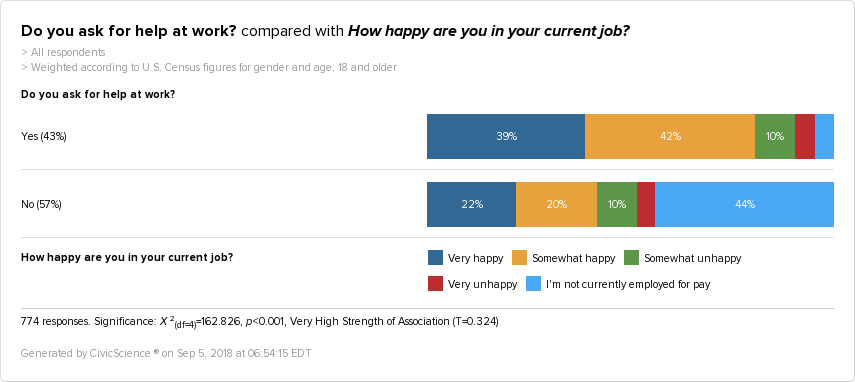

Help and Happiness

That said, there is a direct link between asking for help and job happiness.

Those who ask for help are much more likely to be very happy in their current job, than those who do not. What’s more, 42% of those who do ask for help consider themselves somewhat happy in their job. That is more than double the percentage of those who do not ask for help, but who rate their job happiness the same.

Ultimately, asking for help is not a straightforward task. While the majority of U.S. adults report asking for assistance in some aspect of their lives, inequality regarding who asks for help and where may still be a major obstacle.