The workplace is not typically an environment associated with displays of passionate emotion. Although there may not be explicit rules regarding how employees should handle their feelings, there are certainly some unspoken social norms. CivicScience asked over 16,000 U.S. adults whether it was okay to cry at work, and over 33,000 U.S. adults if they had ever done so before.

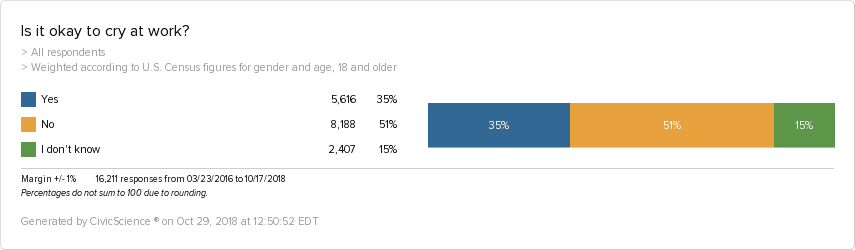

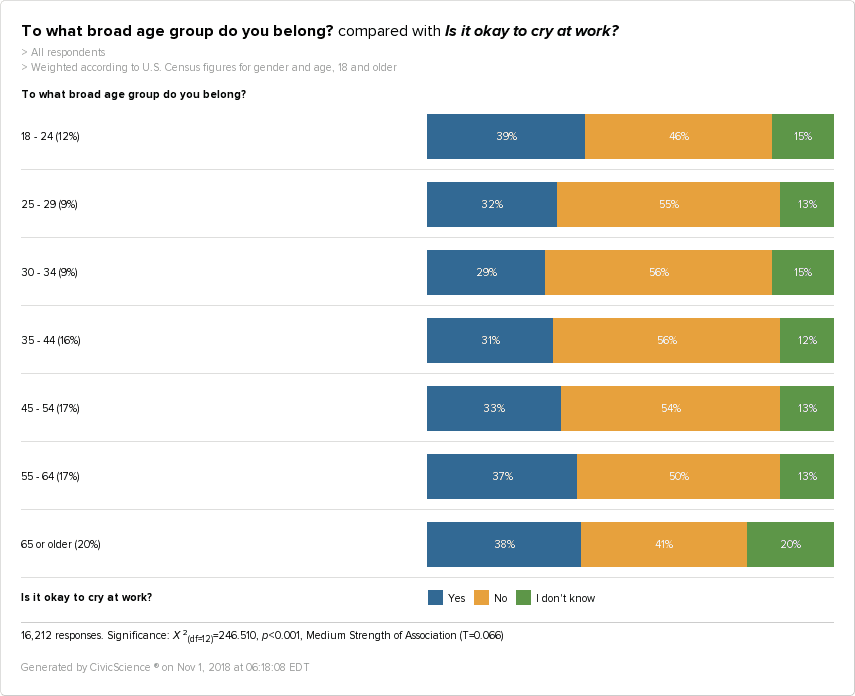

As the data shows, 51% of respondents do not think crying at work is acceptable. The rest of respondents are divided between those who think it’s okay and those who aren’t quite sure.

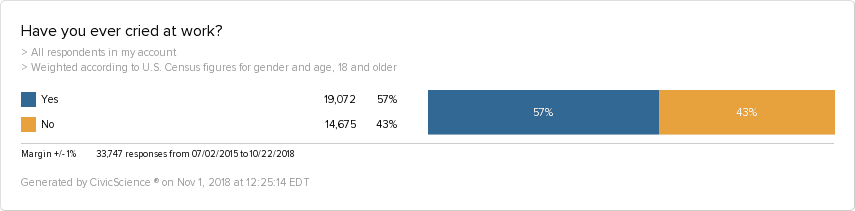

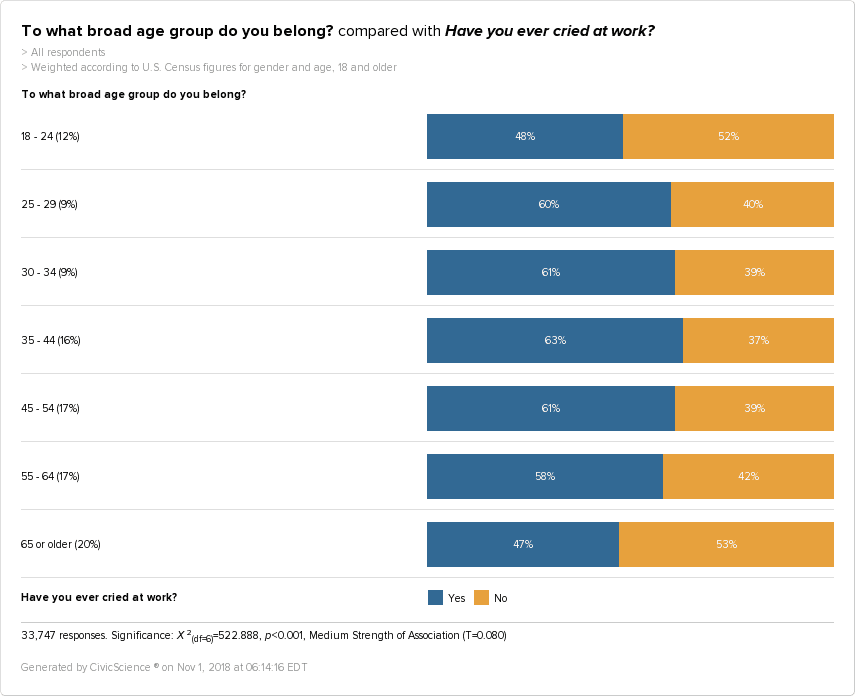

Despite the fact that just over half of U.S. adults disapprove of workday crying, 57% admitted that they have cried at work before. This is the first indication that there is some level of disconnect between what is acceptable in theory and what happens in reality.

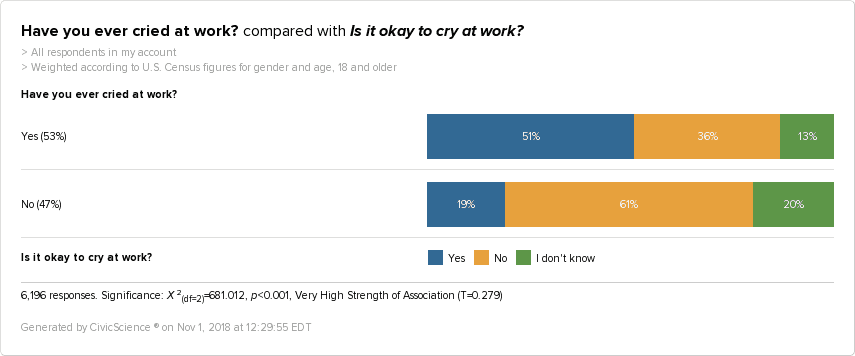

Of those who have cried at work, the majority think it’s ok to do. However, it should be said that 36% of those who have cried don’t think it’s acceptable.

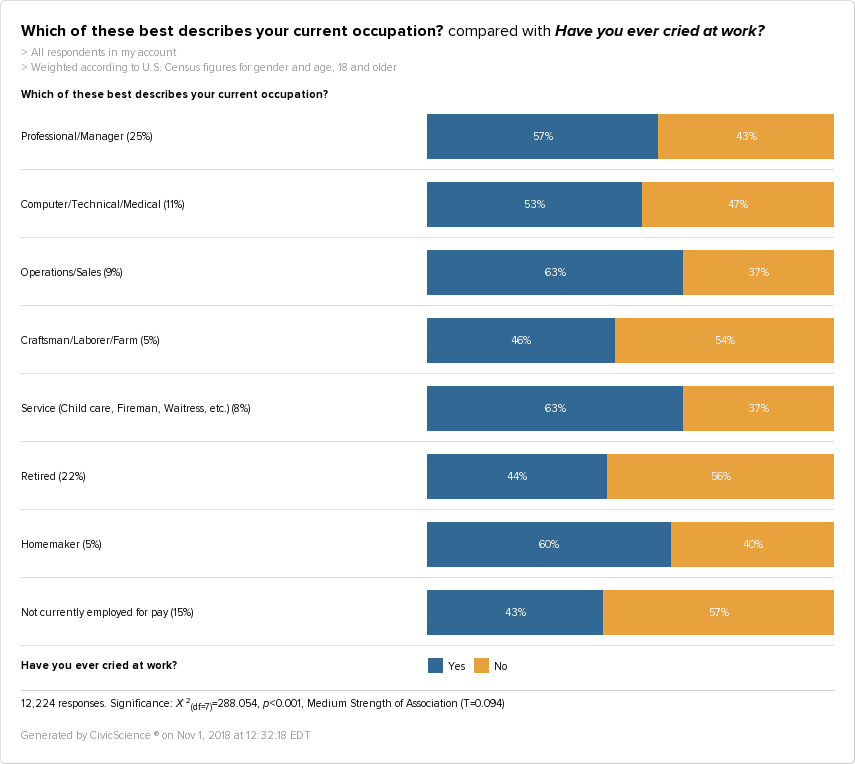

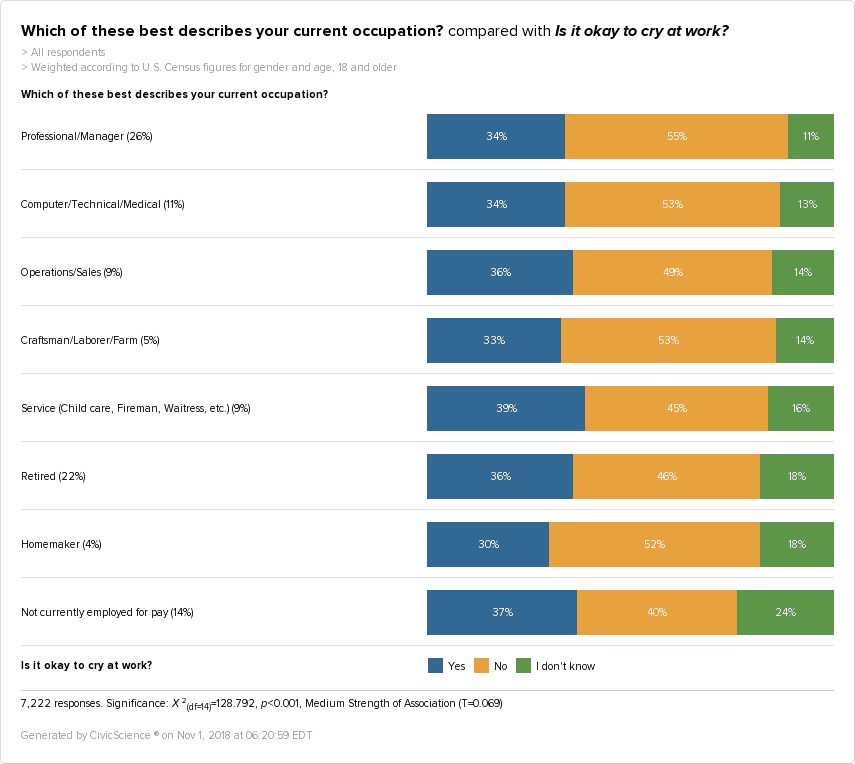

Of course, reasons for crying at work can vary, and occupation is one factor to consider. The data speaks to a variety of vocations, however, there are two to note: U.S. adults in service roles are more likely to say crying at work is okay, while those in professional or managerial roles are more likely to disapprove.

This is not entirely unexpected, given the different skill sets that these different occupations tend to favor. However, the reality for those in professional or managerial roles paints a more dynamic picture of the work environment.

34% of U.S. adults who hold professional or managerial positions have cried at work, outweighing the 30% who have not. This particular group exhibits a disconnect between expectations and reality with regard to the appropriateness of shedding a tear in the office, suggesting a larger cultural conflict could be at play. Although this particular work culture may find crying on the job inappropriate, this same environment creates conditions that make crying more common than in any other workplace.

Softer With Age?

Stage of life could also influence whether U.S. adults feel it is appropriate to cry in the workplace. From the ages of 25 to 34, the percentage of U.S. adults who believe it is okay to cry it work takes a dip into the single digits. This may look extreme, but when taken in context, could seem less so.

After all, these are the years when advancing higher in one’s career is likely the top priority. Still young enough to be unwed and not yet in the throes of parenting, many of the respondents in this category may have a laser focus on advancing their career–and crying at work may not seem like the fastest way to a promotion.

In this case, theory and reality are aligned, suggesting that the 25 to 34 set may be keeping their emotions under wraps, for a variety of reasons.

In terms of life stage, emotions come to the surface around age 35. Approval ratings essentially double in both of the above graphs at that time and only increase from there.

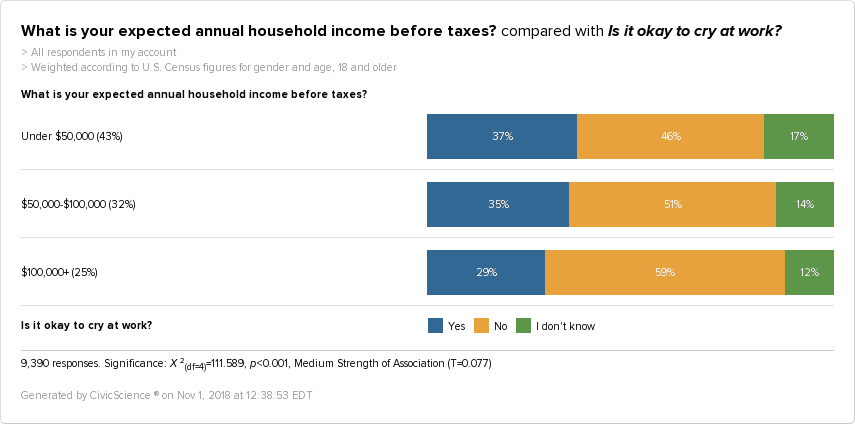

Money Matters

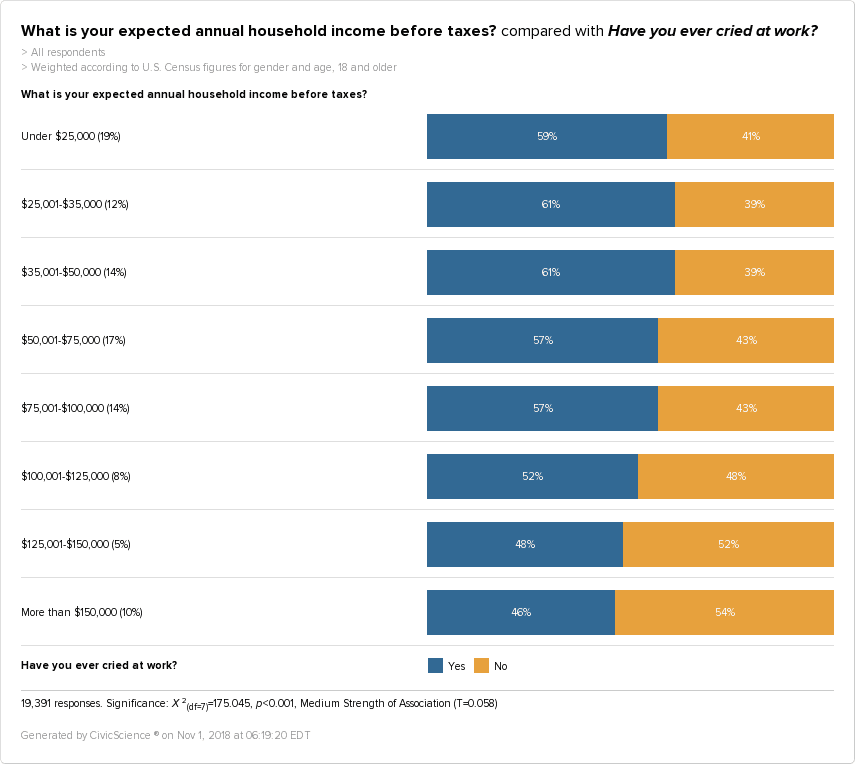

And if crying at work is frowned upon by those trying to level up, it is definitely disapproved by those who have made it, at least financially speaking. As the data reveals, crying decreases in acceptability as income increases.

The lived experience echoes the above data, with low-income earners making up 48% of those who have cried at work. That percentage quickly drops to 32% for middle-income earners and then 20% for those with the highest earning power.

Shedding a tear, especially in a public space, is likely the result of an especially triggering experience. Whether that pressure is internal or external, it seems that those at the lower end of the earning scale may be feeling it more, which could be creating more reason to get a little emotional.

Crying Under Pressure

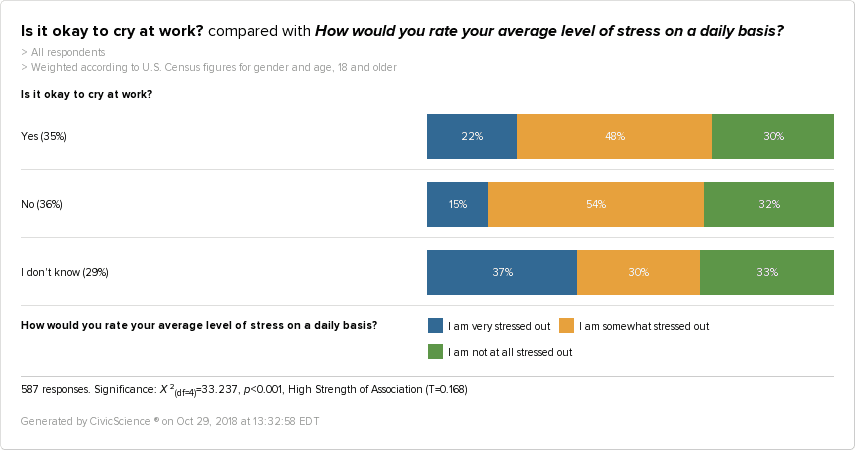

Stress, as we have seen, is very real. However, it is those who consider themselves only somewhat stressed out who make up the highest percentage of U.S. adults who believe it is okay to cry at work. Of course, high levels of stress may not necessarily mean being emotional. In fact, those who are very stressed out are the largest percentage of respondents who are not sure.

The very stressed out respondents are, it seems, keeping it together at work. Despite 22% approving of work-time crying, only 20% have done it themselves. This statistic further suggests that while highly stressed individuals may empathize with those who express themselves through tears, this may not be how they handle stress themselves.

It is the somewhat stressed out respondents who make up the largest percentage of those who have cried on the job. Could those who consider themselves very stressed out simply have so much stress that they are used to managing their emotions? Could those with less stress feel more deeply impacted when things go awry?

Although the data cannot answer these questions directly, it does illuminate issues worth exploring more deeply, either as an individual or as part of a larger company-wide effort to understand the emotional dynamics at play.

What is certain is that crying at work is a very common occurrence–despite general opinion opposing such a passionate display. And while this sort of emotional release is seemingly more common in workplaces where emotional skill plays a larger role and amongst income earners at the lower end of the spectrum, it ultimately speaks to a larger concern regarding work environment, stress culture, and the very human need to process emotions even in the most public of places.