Even–and perhaps especially–during a global pandemic, food continues to be a priority. After all, people will still need to eat. And, as it turns out, how they choose to do so–whether cooking at home or getting delivery –continues to illuminate larger consumer behaviors. CivicScience checked in on the responses of more than 15,500 U.S. adults, to see how their relationship to food delivery could impact future plans.

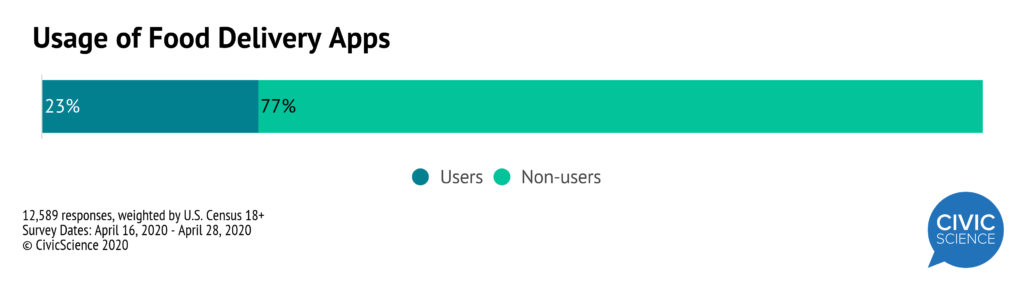

As the data show, 23% of U.S. adults are using food delivery apps. That number is up just 1% from this time two weeks ago, with Gen Z continuing to lead the way.

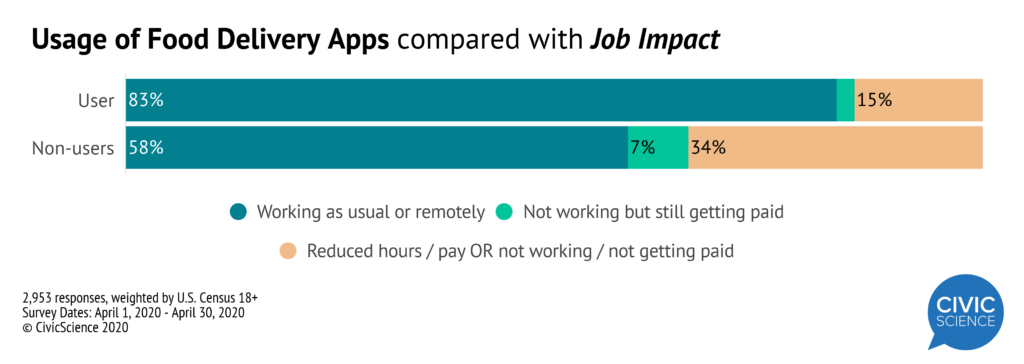

CivicScience data also show food delivery users over-index in likelihood to be working as usual or remotely amid the pandemic. Only 15% report reduced pay or not working at all. Non-food-delivery users show a much greater instance of getting paid less or not working, more than double that of people who order delivery. This suggests that financial flexibility could be impacting delivery usage.

CivicScience data also show food delivery users over-index in likelihood to be working as usual or remotely amid the pandemic. Only 15% report reduced pay or not working at all. Non-food-delivery users show a much greater instance of getting paid less or not working, more than double that of people who order delivery. This suggests that financial flexibility could be impacting delivery usage.

This point aligns with what CivicScience already knows about delivery app users and income: higher-income earners are ordering the most delivery than any other income bracket.

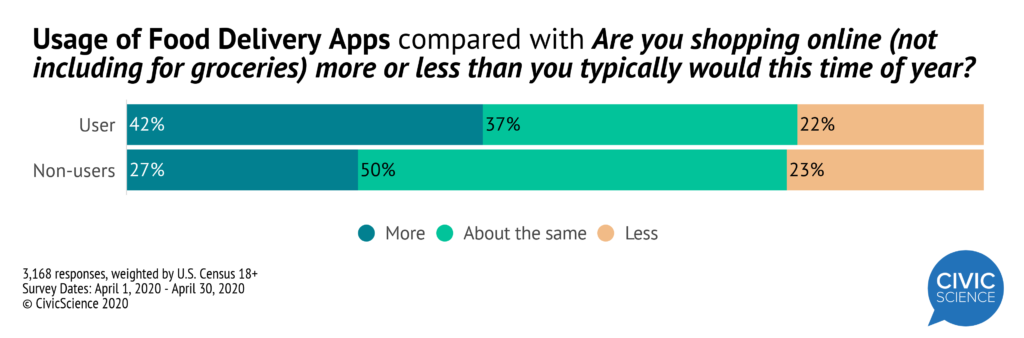

Delivery Correlates to Online Shopping

As it turns out, those turning to delivery apps are also shopping online at a significantly higher rate than non-users.

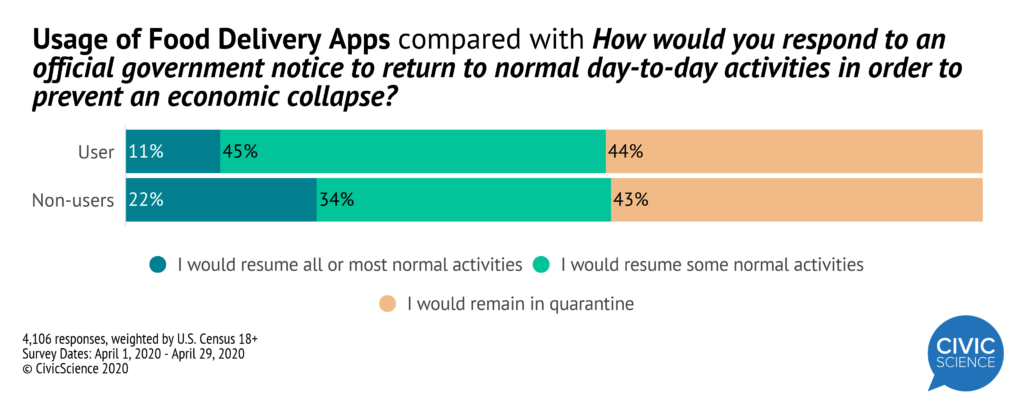

Beyond the basic understanding of the current demographic make-up of food delivery users, however, is the way individuals are inclined to behave once lockdowns are lifted.

Those who have been getting food delivered in the last month express more reluctance to return to all or almost all of their normal activities if an official notice was issued. On the other hand, non-food-delivery users are twice as likely to say they would resume all or almost all of their day-to-days.

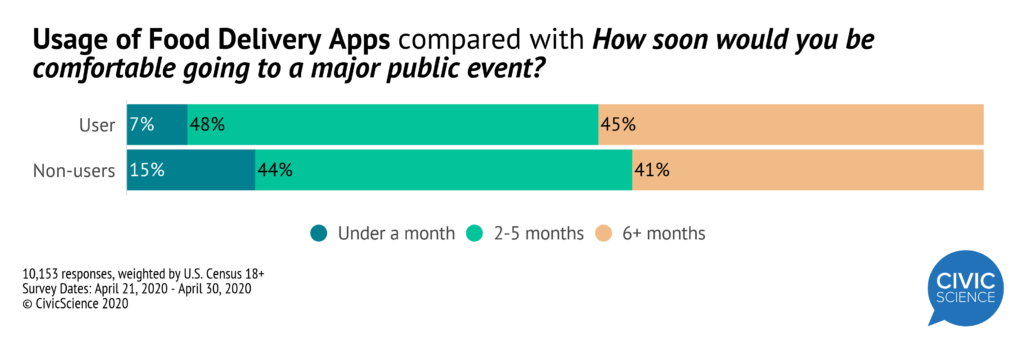

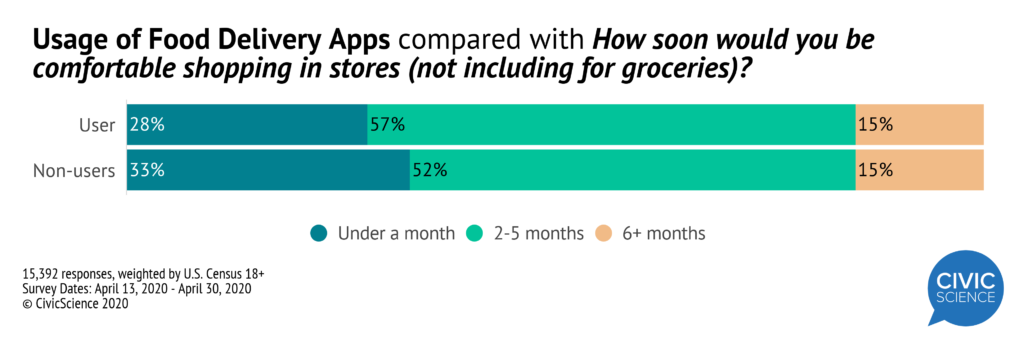

The relationship between people using food delivery services and varying levels of readiness to return to normal life can be seen even more clearly when broken down into specific “normal” activities, such as going shopping and visiting restaurants.

Similar to how the general population polls, activities, such as concerts, festivals and other public events, carry less of a pull for both delivery app users and non-users. Yet only 7% of those who do use food delivery services say they would be comfortable with going to a public event in under a month, compared to 15% of non-users. Those ordering in would prefer to wait 6 months or more to be in such large crowds.

In the meantime, what are shoppers to do? When it comes to non-grocery shopping, 57% of those getting food delivered would ideally wait 2-5 months before resuming non-grocery shopping trips. And they were certainly less likely to shop in a store in under a month.

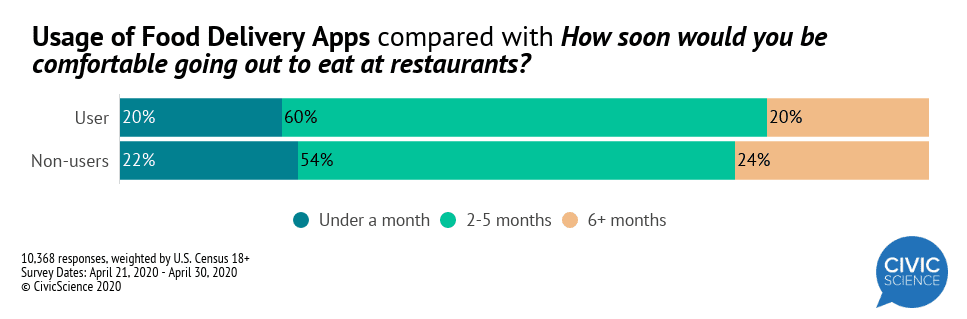

Despite delivery users’ love of takeout, dining in restaurants has even less appeal, with 60% of food delivery users reporting that it could take anywhere from 2-5 months for them to become comfortable eating in restaurants again.

This is a key insight for restaurants who participate with delivery services. It’s also motivation for restaurants, who did not have delivery options prior to the pandemic, to start thinking about how they can improve delivery and retain their customers.

Overall this data suggests that American adults using food delivery services are a little more cautious than non-food-delivery users to get back out into the world.

And when it comes to dining in restaurants, those still ordering delivery are in fact the more hesitant to sit down in person for the foreseeable future.