Temporary economic collapse, fear of a plague, fear for your family members’ health–all of these things are objectively awful but could be tempered by an idea of an end date. We all need something to look forward to. None of us have that, other than a vague notion of looking forward to this all being over next month, or next fall, or next year.

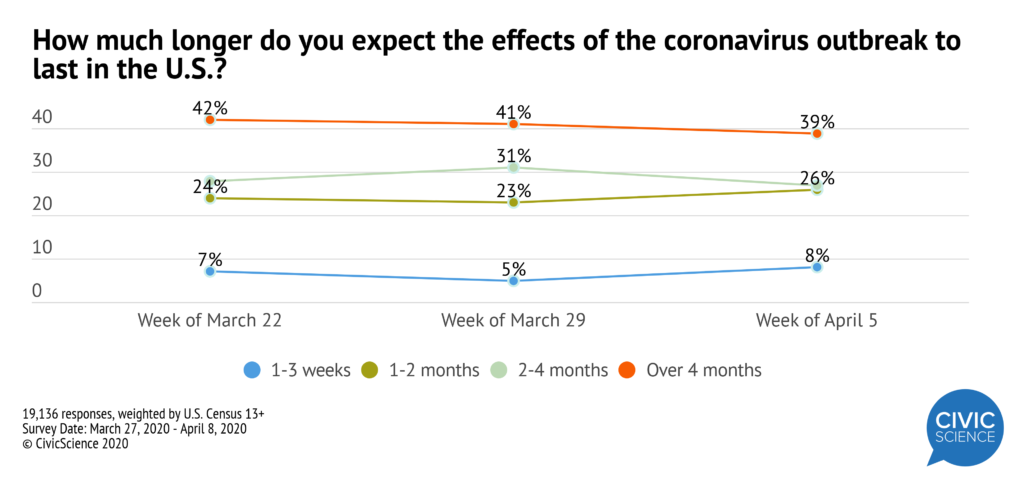

The population is also split on how optimistic they should be and it doesn’t seem to be stabilizing. The week of March 29, the number of people who thought it would be over in a few weeks halved, indicating that the reality of the situation was likely setting in. The week of April 5, though, that number is back up to where it had been previously, perhaps in reaction to some of the news about hospitalization rates decreasing in New York City, despite officials warning that it’s too early to say how significant this is.

It’s impossible to say if the trend will continue. Each day brings news that changes the way we view the virus, its spread, and its likelihood to drag on for days, or months, or weeks. Social media usage is increasing among the U.S. population during the pandemic (likely to unhealthy levels) to the point where 50% of people say they’re using it more now.

That means every post, every piece of information (real or fake, verified or speculative) has the potential to impact millions of people’s perceptions of just how bad this is going to get and for how long. “Fake News” was weaponized after the 2016 election by both political factions to the point where it’s completely lost its meaning, but if there was ever an argument for cleansing the timeline of speculative “reporting,” a global pandemic certainly drives home its importance.

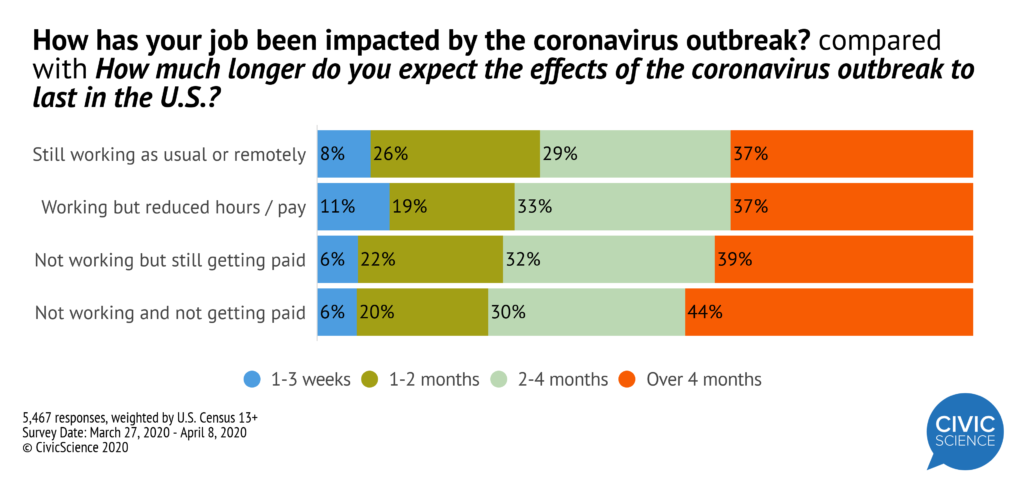

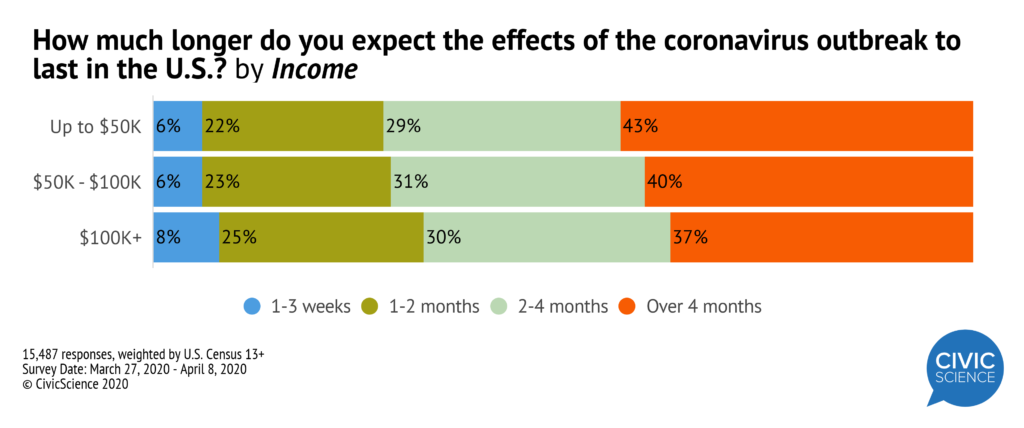

In the meantime, all we can do is analyze the information as it comes, and it appears that the biggest divide on how long this thing will last is caused by your employment status and your income levels. Americans who have lost their jobs and are no longer receiving income are more likely to think this is going to last a long time, likely because they figure if it’s bad enough that they’ve lost their jobs, it must mean that the businesses that employed them are bracing for an extensive period of hardship. Similarly, those with more money have to a lesser extent convinced themselves that this will be shorter than those with under $50,000 in income.

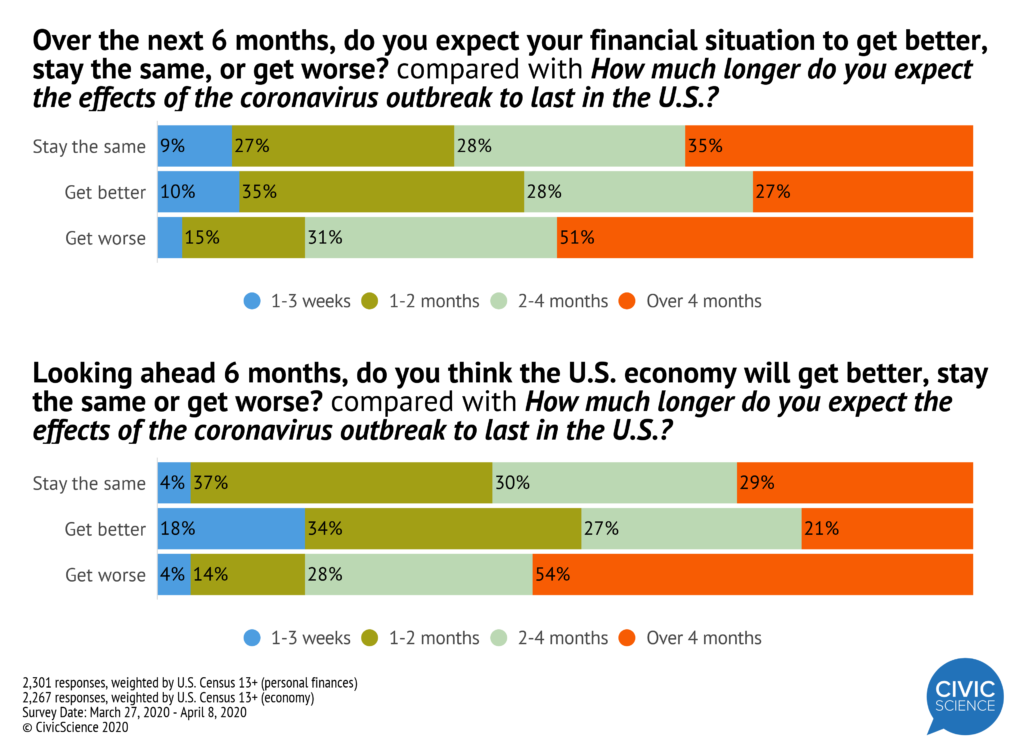

Given the continued uncertainty and the fact that none of this data is static, it’s hard to imagine this trend of optimism continuing. Jobless claims continue to rise exponentially, both in CivicScience’s data as well as reported data from the Department of Labor. As more employment situations are impacted, more pessimism will enter the public consciousness, helping to fuel the lowest recorded score in the history of the Economic Sentiment Index. In fact, it’s hard to call it pessimism so much as realism: the longer this goes on, the worse it will get for an economy that does not appear prepared for this type of ongoing freeze on commerce. And those that feel that the economy will get worse, or their own personal financial situation will get worse, are the ones that are significantly more likely to think that this ordeal will last many more months.

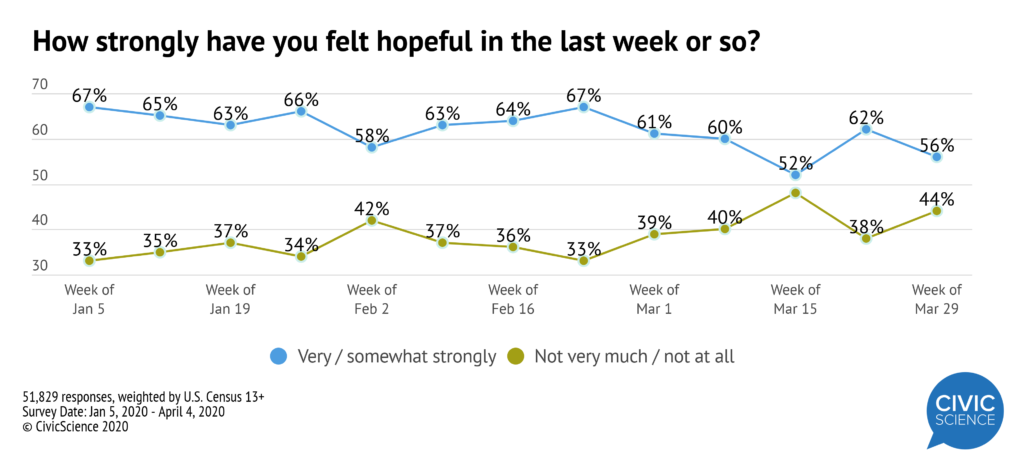

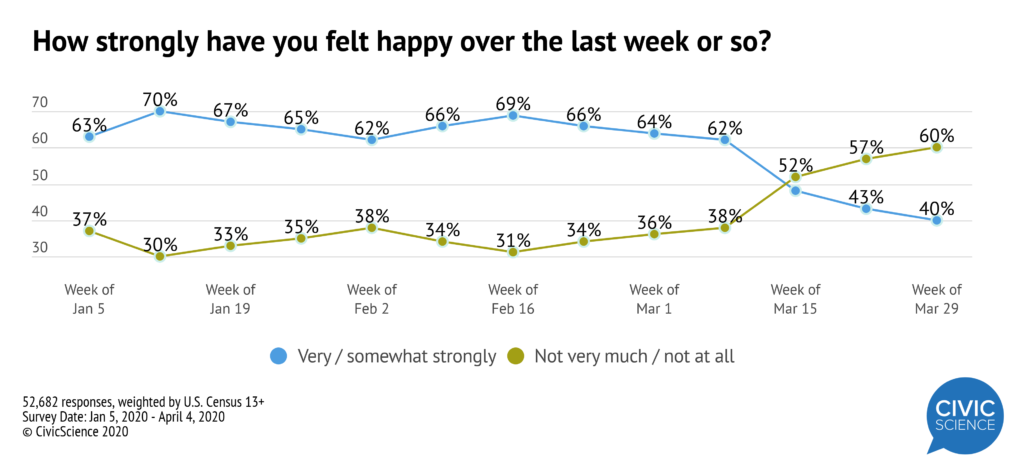

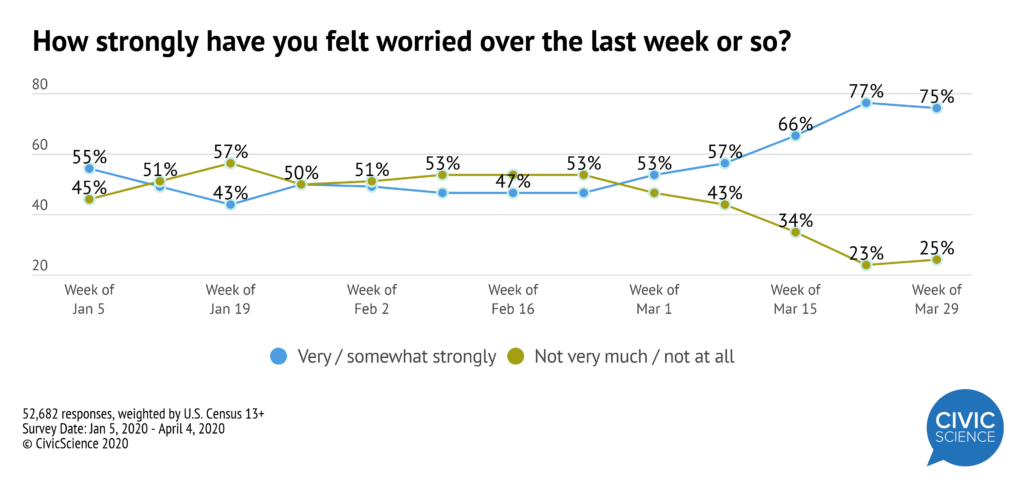

Given the continued uncertainty and the fact that none of this data is static, it’s hard to imagine this trend of optimism continuing. Jobless claims continue to rise exponentially, both in CivicScience’s data as well as reported data from the Department of Labor. As more employment situations are impacted, more pessimism will enter the public consciousness, helping to fuel the lowest recorded score in the history of the Economic Sentiment Index. In fact, it’s hard to call it pessimism so much as realism: the longer this goes on, the worse it will get for an economy that does not appear prepared for this type of ongoing freeze on commerce. And those that feel that the economy will get worse, or their own personal financial situation will get worse, are the ones that are significantly more likely to think that this ordeal will last many more months. Where does that leave us? American emotions are worse than they’ve ever been. For the first time since CivicScience began tracking emotional states, more Americans are unhappy than happy. Hopefulness looks more like a roller coaster blueprint than it does any sort of reliable trend monitor over the past 3 weeks, again lending credence to the idea that the onslaught of news is just confusing people and muddying the waters on how optimistic we’re supposed to be. Worry is trending in the right direction, but it’s got a lot of ground to cover to make up for the exponential increase it’s seen since the start of March.

Where does that leave us? American emotions are worse than they’ve ever been. For the first time since CivicScience began tracking emotional states, more Americans are unhappy than happy. Hopefulness looks more like a roller coaster blueprint than it does any sort of reliable trend monitor over the past 3 weeks, again lending credence to the idea that the onslaught of news is just confusing people and muddying the waters on how optimistic we’re supposed to be. Worry is trending in the right direction, but it’s got a lot of ground to cover to make up for the exponential increase it’s seen since the start of March.

In the world of research, one of the most important things you can provide is a benchmark. It gives people assurance that some new phenomenon or behavior is comparable to what came before it. Multi-million dollar decisions are made based on benchmarks and the confidence that this new, never-before-seen thing can be compared to a past phenomenon at a high level of statistical certainty. Unfortunately, as we are learning on the fly, there is no benchmark for this. We are in completely uncharted territory. The best we can do is document it, analyze it in real time, and adapt as quickly as possible.

In the world of research, one of the most important things you can provide is a benchmark. It gives people assurance that some new phenomenon or behavior is comparable to what came before it. Multi-million dollar decisions are made based on benchmarks and the confidence that this new, never-before-seen thing can be compared to a past phenomenon at a high level of statistical certainty. Unfortunately, as we are learning on the fly, there is no benchmark for this. We are in completely uncharted territory. The best we can do is document it, analyze it in real time, and adapt as quickly as possible.