The Gist: A recent H&M slump put the viability of the fast fashion clothing industry into question, but data indicates that growing concern over company social consciousness isn’t likely to be turning away shoppers.

Swedish “fast fashion” company H&M, the world’s second-largest clothing retailer, made headlines earlier this year when it announced the closure of 170 of its stores. The move led some to call into question whether or not fast fashion as a whole, characterized by trendy, inexpensive clothing and rapid production turnover, is on its way out.

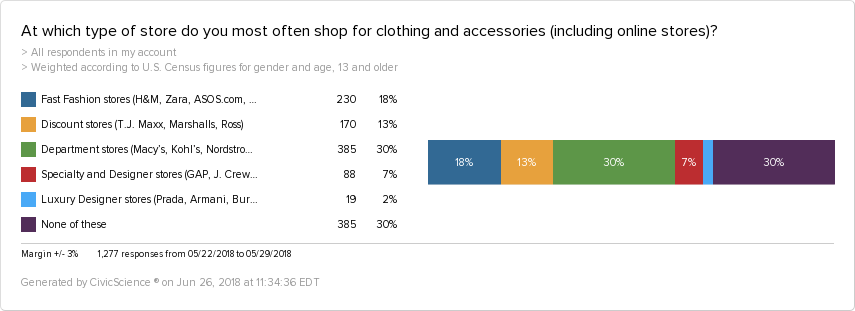

We looked broadly at shopping habits among popular clothing sellers and found that 18% of U.S. respondents aged 13 and up shopped most often at fast fashion stores, such as H&M, Zara, and Target.

That’s less than those who shop most frequently at department stores (30%) and those who shop most frequently at stores not accounted for in the survey (30%), perhaps such as Amazon, eBay, and boutiques, independent labels, or second hand stores (which we covered in a previous post).

Still, fast fashion seems to be more popular than discount stores, such as T.J. Maxx and Marshalls, and significantly more favored than specialty and designer stores, such as GAP, J. Crew, and Urban Outfitters, or luxury designer stores.

While we can’t determine whether or not the 18% of fast fashion lovers represent a loss or a growth for fast fashion at this point, what we can see are other trends that provide some, well, interesting but rather confusing insights.

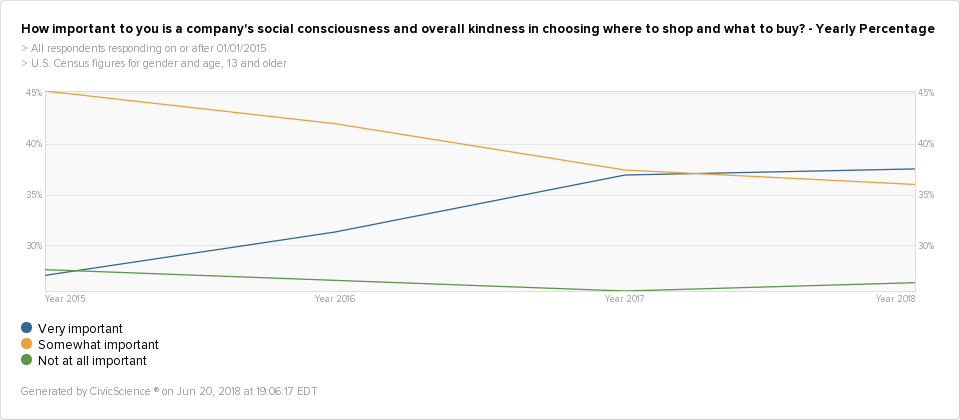

First, let’s talk about ethics. Data shows that a company’s social consciousness and overall kindness have become increasingly important to Americans over the past three years; today 38% say that it’s “very important” (blue line), outweighing those who say it’s “somewhat important” and far surpassing those who think it’s “not at all important.”

Given the fast fashion production model, which has been mired in bad press involving questionable overseas labor practices and environmental concerns, you might assume that fast fashion shoppers would be the least concerned with social consciousness. In fact, the opposite is true.

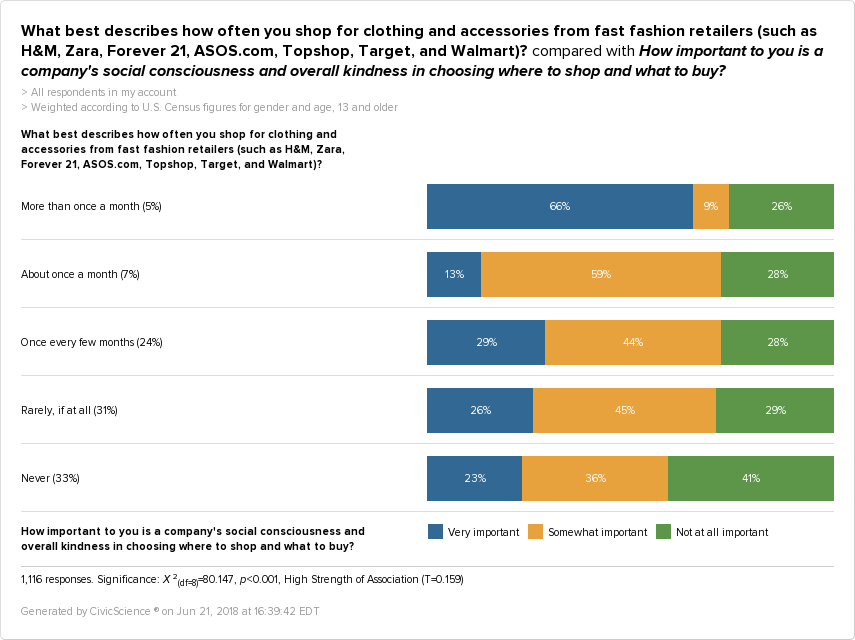

Looking at how frequently the public shopped for fast fashion items, we found that the most frequent fast fashion shoppers (those who shop for clothing and accessories at fast fashion stores more than once a month) are by far the most concerned with company social consciousness and overall kindness. The majority of the most frequent shoppers (66%) said that company social consciousness was “very important,” compared to only 23% of those who never buy fast fashion.

We can also see that more infrequent fast fashion shoppers — those who shop once every few months or on rare occasion — together make up the majority of shoppers surveyed (55%), and share similar views on company social consciousness as well; close to 30% of both groups view it as important while about 45% view it as at least somewhat important.

The anomaly here is the once-a-month shopper group. Only 13% see company social consciousness as very important, while 59% see it as somewhat important.

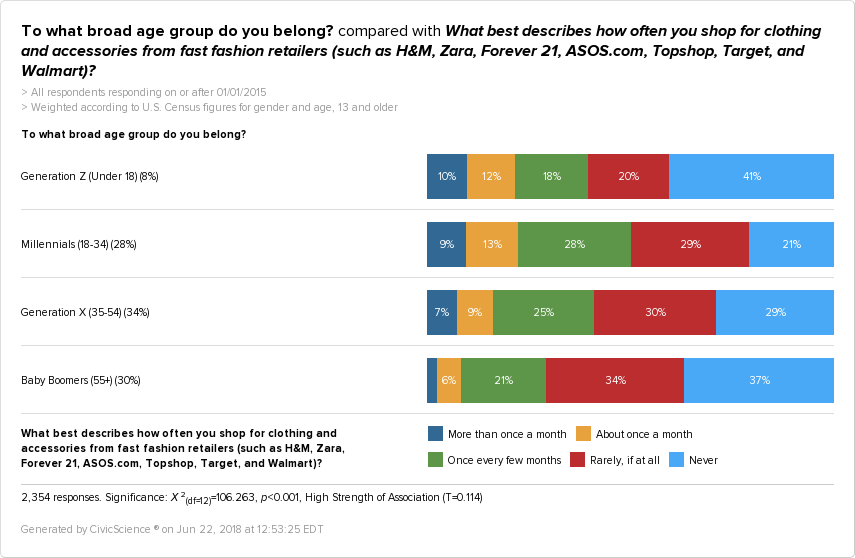

How to make sense of these numbers? Age matters, for one. Our data shows that the younger generations (Millennials and Gen Z) value company social consciousness slightly more than other age groups, with the 18-34-year-old cohort valuing it the most. Those generations are also the most frequent fast fashion shoppers, again with the youngest Millennials (18-34 year-olds) taking the lead:

Looking at gender is further illuminating. Our data tells us that women are much more likely to be concerned with company social consciousness, making up 60% of those who say it’s very important compared to 40% men.

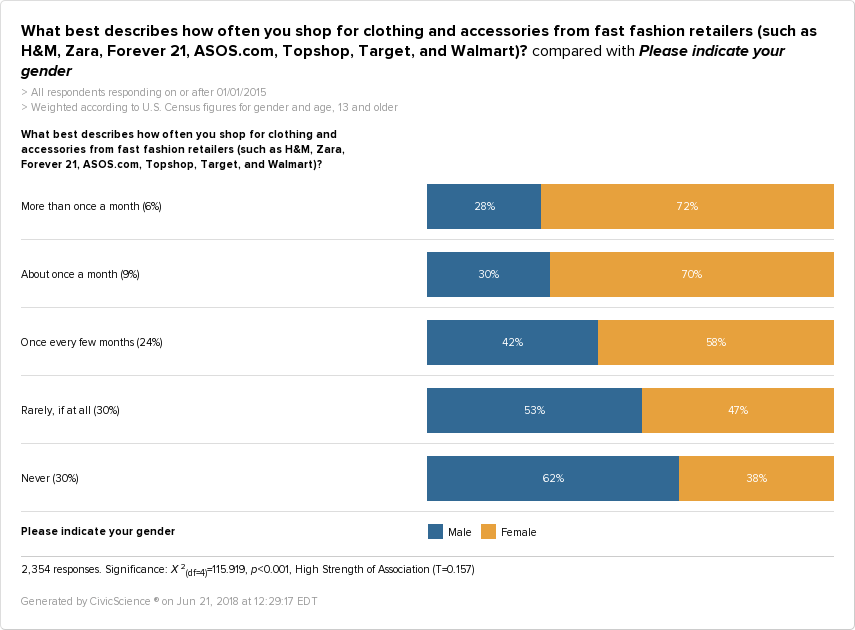

At the same time, women comprise a strong majority (72%) of the most frequent fast fashion shoppers, as seen here:

Overall, we see a case of “consumer dissonance,” if you will. It appears that fast fashion shoppers (especially 18-34 year-olds and women) lured by the trendy, affordable offerings of fast fashion are also simultaneously the most concerned with ethical practices — two things that have historically been viewed as mutually exclusive.

Perhaps fast fashion shoppers aren’t aware of the issues that have surrounded the industry, or maybe they now hold a more positive view of fast fashion retailers, many of whom are vowing to make changes to improve sustainability.

Whatever the case, it’s not clear that concerns over company social consciousness are driving shoppers from H&M or other fast fashion brands.

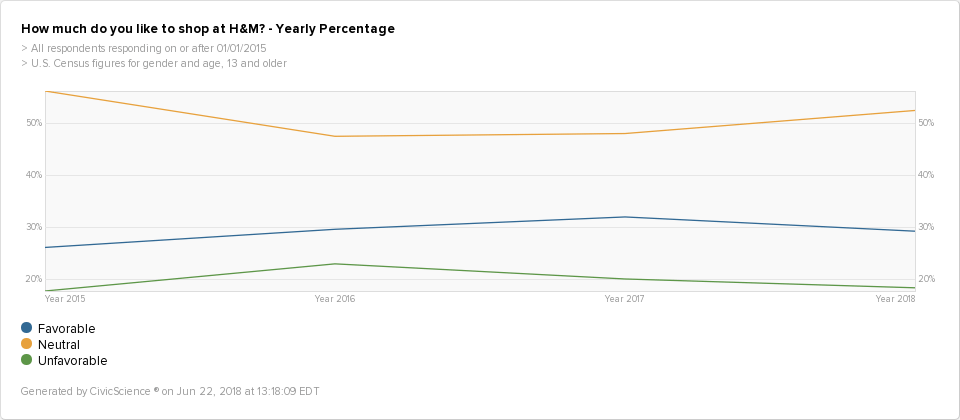

In fact, when it comes to H&M, we aren’t seeing a decline in favorability within the past couple years. Check out the blue line below, showing those who are favorable to the brand.

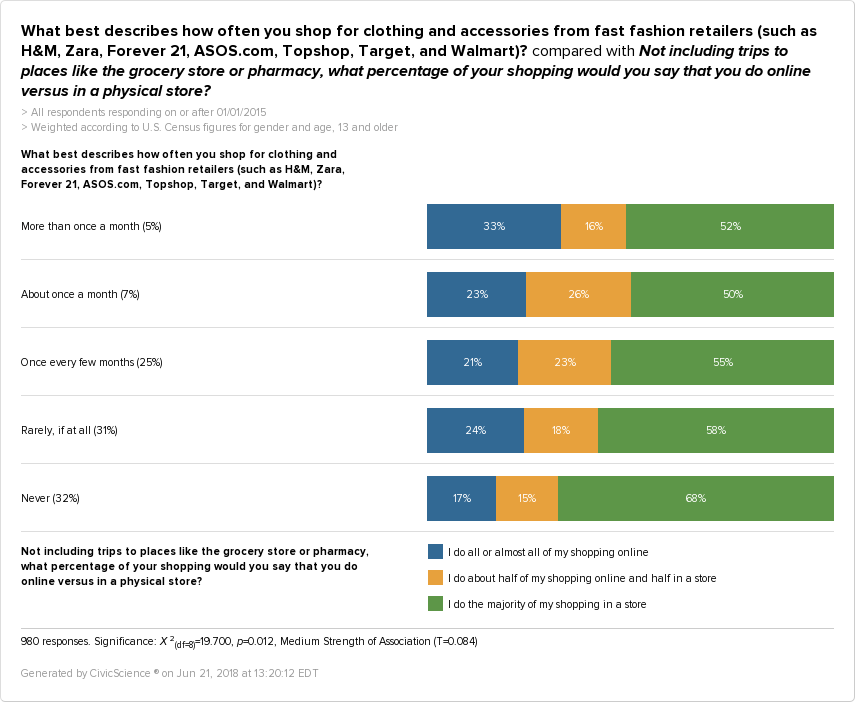

What’s more, new fast fashion retailers are popping up and gaining traction, such as Boohoo.com. That point brings up something else retailers should consider when it comes to fast fashion: online shopping. We found that fast fashion shoppers are significantly more likely to shop online than in stores (for retail in general) than non-fast fashion shoppers, with the most frequent fast fashion shoppers doing the most online shopping (33%).

All in all, with the trend towards increased social consciousness, it’s plausible that taking a tougher stance on labor conditions while still managing to keep prices low would likely help fast fashion retailers like H&M to keep and attract new customers. However, it’s not evident right now that some sort of massive sea change in consumer awareness is leading to fast fashion’s demise.

Retailers should consider the proclivity toward online shopping among the fast fashion crowd, as well as other trends that could affect sales, such as clothing shoppers who value quality and durability above all else (which we’ve covered in detail) and Millennials opting to spend more on experiences over goods.